Gentianella quinquefolia

Quick facts

Common Names

Family

Dormancy Type

Simple & reliable pretreatment protocol

Quick pretreatment protocol

Sowing temperature regime

Light requirement for germination

Days to first germination

Weeks to fill Nursery Pot

How to Grow Gentianella quinquefolia (Stiff Gentian, Agueweed) from Seed

Gentianella quinquefolia is relatively secure here in southern Wisconsin, but it is rare across the states of New England. Where I live in Dane County, I often find it in high-quality prairie remnants (and indeed, its coefficient of conservatism in Wisconsin is 7). So I feel that G. quinquefolia gives my planting beds that ineffable “remnant” look. I’ve also seen at least one credible report of Rusty-patched bumble bees (Bombus affinis) nectaring on G. quinquefolia, and I’ll plant almost anything to entice a rusty. I seldom see G. quinquefolia in the nursery trade, so growing it yourself is often the only option.

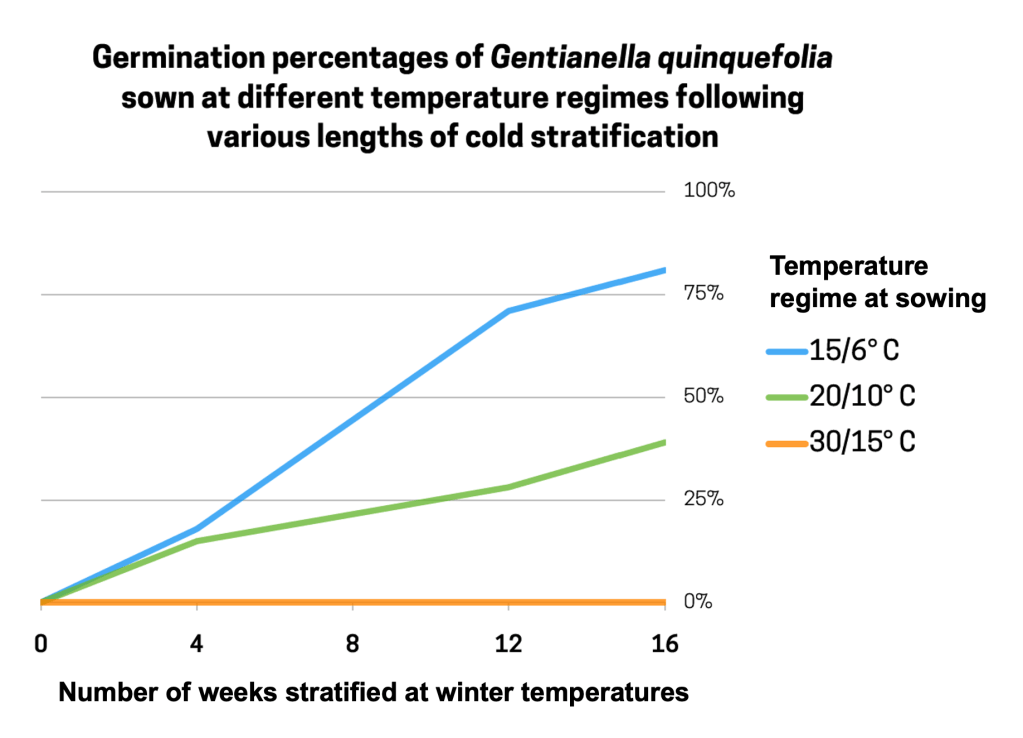

G. quinquefolia is relatively easy to grow from seed, but it’s slow, and it’s picky about sowing temperature. Baskin & Baskin, in their 2005 study,2 reported germination results for G. quinquefolia that suggest the seeds require two conditions to achieve relatively strong germination (see figure 1):

- About 12 weeks of cold stratification (5° C)

- A cool temperature regime (15/6° C) at sowing (see this post for more info on temperature regimes)

The search for a faster germination protocol

12 weeks is a relatively long stratification requirement, and considering that the seedlings grow slowly (see figure 2), you might need to start stratifying your seeds in November to ensure sizeable plants by April/May. For those amongst us who start thinking about seed starting in January of February, three months is longer than they can afford to wait (especially considering that G. quinquefolia take about four months to reach transplantable size).

So I set out to determine whether gibberellic acid (GA3) could substitute for cold stratification in promoting germination, thus reducing pretreatment time. I purchased one packet (~400 seeds) of G. quinquefolia seeds from Prairie Moon, and I split the seeds into two groups: 200 seeds for the control group, 200 seeds for the GA3 group.

For the GA3 group, I soaked the seeds in a 250ppm GA3 solution for 24 hours, then rinsed them with water. For the control treatment, I soaked in plain water for 24 hours. Each group was then mixed with damp sand and placed in my fridge (~5° C). I tested each group twice: once at 4 weeks and once at 6 weeks. For each test, I germinated the seeds at a temperature regime of 15/6° C (14-hour day, 10-hour night) with artificial light provided during the day.

Results: GA3 drastically increases germination for seeds given a shortened stratification period

GA3-soaked seeds germinated at a percentage approximately three times greater than the control group (see table below). So whether you’re a production grower or a hobbyist, if you’re pressed for time, GA3 will give you more germination in less time.

Below is a table of my results. Note that these cannot be compared directly to Baskin & Baskin’s results; whereas Baskin & Baskin incubate seeds on filter paper in petri dishes and consider emergence of the radicle to be germination, I test my seeds in growing medium (PRO-MIX BX) and I only count seedlings that survive to grow true leaves (i.e., I don’t count seedlings that abort or fail to grow true leaves). So my “real world” germination will be lower than lab germination.

| Treatment | Weeks stratified | Germination percentage | Days to first germination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4 | 8% | 14 |

| Control | 6 | 13% | 15 |

| 250 PPM GA3 | 4 | 26% | 11 |

| 250 PPM GA3 | 6 | 36% | 9 |

While a germination rate of 26% may not seem very impressive, consider the fact that Prairie Moon sells G. quinquefolia in packs of 400 seeds for $3.50. Also note that these are tiny seeds, so small that I needed to use a loupe to see germinants. I sowed these on a porous growing medium, so who knows how many seeds fell into little cracks and got buried too deep.

Planting considerations

Although it is relatively simple to keep G. quinquefolia happy in the greenhouse, I have found that they have a tendency to die when planted out into the field. My theory is that they are sensitive to sun in the basal rosette phase of their lifecycle (i.e., their first growing season). Even though they grow in the open prairie, they spend their first growing season in the “understory” of the prairie, sheltered by other plants. So try planting them in a spot there they get sheltered—but not smothered—by their neighbors. In remnants, I find them near short-stature plants typical of Wisconsin dry-mesic prairies such as:

- Pedicularis canadensis (wood betony)

- Drymocallis arguta (prairie cinquefoil)

- Symphyotrichum ericoides (heath aster)

- Solidago ptarmicoides (upland white aster)

- Pulsatilla nuttalliana (American pasqueflower)

- Primula meadia (shooting star)

- various shorter grasses and sedges

If you know of any particularly good companion plants, I’d love to know!■

Have a question? If you have questions about Midwestern native plant propagation that you want answered in a future post, I’d love to hear from you! Shoot me an email at plantpropagationproject@gmail.com

Want to support this work? Buy me a cup of coffee (or a bag of potting medium) with the donation button at the bottom of this page. Or better yet, send me your germination success stories.

Notes

- I have inferred the intermediate complex subclass based on this experiment. Reported as morphophysiological dormancy in: Carol C. Baskin and Jerry M. Baskin, Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and, Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, Second Edition (Academic Press, 2014), 739. ↩︎

- Carol C. Baskin and Jerry M. Baskin, “Seed Dormancy in Wild Flowers.,” in Flower Seeds: Biology and Technology (CABI, 2005), 171, https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851999067.0163. ↩︎

- Same as above. ↩︎

Buy me a cup of coffee, a whole bag of coffee, or a whole bag of PRO-MIX BX (my preferred potting medium).

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you for supporting this project!

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly